The next morning, since we were up early to ship our package from the old post office, we tried a local bakery for breakfast. Then we got the car and went off to our destination for the day, Bath. There, Vere wanted to wash a few clothes at a laundromat, as there isn’t one in Cheddar; and while that was getting done, we sat and had an early lunch at the café next door. When both the clothes and lunch were completed, we drove closer to downtown where we parked in a major underground lot so we could walk to all the places we wanted to visit.

Our first site? The Roman Baths. We had both visited them before, but those visits were in the 1980s, when there were very few tourist accommodations. Then, a simple stairway descended to the baths. Today, there is a major museum with aluminum walkways and channels for tourists to follow.

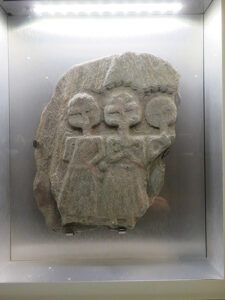

The Roman Baths museum collection contains thousands of archaeological finds from pre-Roman and Roman Britain. We walked through the semi-darkened rooms of the museum with its many displays. Two of the carvings were from pediments around the Temple courtyard, one of the lunar goddess Luna and the other of the sun god Sol. There was also a small carving of three Celtic mother goddesses.

Bathing during the Roman occupation in Bath was a major part of Roman living. It was done by moving from one set of progressively heated rooms and hot tubs to another, with a cold plunge at the end. The warm rooms were called a tepidarium, hot tubs were called a caldarium, and the cold room with water was a frigidarium. There was also a dry heated room called a laconicum, where one could splash water to make it a steam room. One might also receive an oil rubbing treatment, and when completed, a curved metal tool called a strigil was used to scrape away the oil, sweat, dirt, and dead skin, to invigorate and clean the body.

The water in Bath was fed from a sacred spring and flowed to the bath house. There, the water was channeled under a raised floor. Underneath was a cavity raised up by pilae (stacks of stone or tiles) where heat was forced through by a furnace where a fire was continually stoked. The more the water flowed, the warmer it got, until it reached the large hot pool, five and a half feet deep, which was lined with forty-five thick sheets of lead to hold the heat. Both men and women used the tubs at the same time, and a separate section was reserved for families.

Even before the building of the baths, an embankment of earth projected out at the spring and trailed down the hillside. Roman engineers built this area up with oak piles and stone chambers to support it, and it was covered by a barrel vaulted roof. What was created was a temple dedicated to the goddess Sulis Minerva, a combined Celtic and Roman Goddess, who was believed to protect the hot springs and offer healing powers to those that came to her temple. It dated from the 1st century CE and was built in the classical style. It once stood on a podium about six feet above the courtyard with four fluted Corinthian columns that held up a decorated pediment. A large door led to a cellar where the goddess statue stood. Perhaps the most impressive piece in the museum was the bronzed head of Sulis Minerva.

Even before the building of the baths, an embankment of earth projected out at the spring and trailed down the hillside. Roman engineers built this area up with oak piles and stone chambers to support it, and it was covered by a barrel vaulted roof. What was created was a temple dedicated to the goddess Sulis Minerva, a combined Celtic and Roman Goddess, who was believed to protect the hot springs and offer healing powers to those that came to her temple. It dated from the 1st century CE and was built in the classical style. It once stood on a podium about six feet above the courtyard with four fluted Corinthian columns that held up a decorated pediment. A large door led to a cellar where the goddess statue stood. Perhaps the most impressive piece in the museum was the bronzed head of Sulis Minerva.

During the 2nd century, small side chapels were added. Its courtyard was used as a place of worship and sacrifice. But as Christianity gained popularity, the temple’s use declined, and in 391, Emperor Theodosius ordered all pagan temples closed. The temple fell into a state of disrepair and eventually collapsed in the 6th or 7th century, but the oak piles sank and today still support a stable foundation. In the 12th century, the King’s Bath was built using these foundations. Bathers could sit in a tub up to their necks, and in the 17th century, a stone seat known as the Masters Chair was donated, for the supposed use of the King, along with his noblemen.

Changes and improvements took place through the years, but the place maintained its prestige as curative baths through the 20th century. The original Roman drain from the baths, lined with wooden boards, still empties into the River Avon. Many important finds have been found along this drain, including thirty-four gemstones and a tin mask. Today, a statue of King Bladud, the founder of the City of Bath and the mythical discoverer of its waters, stands over the baths.

The most impressive part of the place is the large pool, itself, which one can see from an outside balcony.

We walked all the way through the building that had been refitted as a museum with hallways of displays and metal walkways over preserved archaeological parts of the building foundations and the baths. We descended by metal stairs to the pool areas and were able to walk around the large pool to see the light-green water surrounded by pillars and steps that went into the pool all around it.

We walked all the way through the building that had been refitted as a museum with hallways of displays and metal walkways over preserved archaeological parts of the building foundations and the baths. We descended by metal stairs to the pool areas and were able to walk around the large pool to see the light-green water surrounded by pillars and steps that went into the pool all around it.

On the far side of the pool, we saw a woman authentically dressed in Roman clothes.

By the time we reached where she was seated, she was replaced by another woman whom we did not get a picture of, but we stopped and chatted with her. We began by asking how often someone goes into the water, either by accident or design, and she said surprisingly often. She called herself Rosina Aventina (named after a minor Roman agricultural goddess), and she described her life. She was a free woman, who lived with a Roman but had decided not to marry him because she liked her freedom. The tribe she belonged to was of the Gaul branch. She was a jeweler working on a buckle for a soldier. She actually had one in her hand that she folded a leather strand around the entire time that we spoke with her.

We carried on quite a long conversation with her about us traveling with our own “wagon” to discover the Roman world and its history. She asked what we did. I explained that my husband made pictures of everywhere we traveled, and I wrote about them. That he also did tax work. She got a surprised look on her face and replied, “the Roman government must love you!” We talked about some of the ancient historians, such as Pliny, Plutarch, Livy, and Augustus. How we loved to sometimes celebrate the old gods, and mentioned parties that we had actually held, celebrating Jupiter, Saturn and others. We told her we had a friend who took on the magical name of Sulis (true). That surprised her and she asked even more questions. It was fun chatting with her, trying our best to speak of things that a person in her time would understand, and she never broke character.

We ended up, of course, in the bookstore, purchased a few books and then we walked around the corner to the Bath Cathedral. We sat on a pew to rest for a few minutes before walking around, placing our heavy bag of purchases next to us. Just as we sat, a woman stepped up to the pulpit to welcome everyone. She explained that she was a volunteer church chaplain. She asked all to take a few moments to pray for all those people on the planet who were starving, homeless, in war, or diseased. It actually brought tears to my eyes. That evening when I went to the church website for some background information, I stared at the message from the church rector, who was quoted as saying, “Come unto me, all you who are weary and are heavy laden.” Which is exactly how we had arrived.

Now on to some background about the Bath Cathedral. There has been a place of Christian worship on this site for twelve hundred years and it has undergone many transformations during that time. Its history stretches as far back as Anglo-Saxon times. In 1088 CE, John of Tours, the Bishop of Wells, was given a monastery at Bath. He ordered the building of a large new cathedral, which was to replace the Saxon abbey. In 1244, Bath was given cathedral status and became one of the most important churches in the area.

Now on to some background about the Bath Cathedral. There has been a place of Christian worship on this site for twelve hundred years and it has undergone many transformations during that time. Its history stretches as far back as Anglo-Saxon times. In 1088 CE, John of Tours, the Bishop of Wells, was given a monastery at Bath. He ordered the building of a large new cathedral, which was to replace the Saxon abbey. In 1244, Bath was given cathedral status and became one of the most important churches in the area.

Building by different abbots continued. In 1539, when King Henry VIII closed the abbeys, convents, and monasteries, the monks were forced to leave, and the cathedral was left to decay. In 1573, Queen Elizabeth I gave permission for a national collection to raise money for the restoration of the abbey, and by 1620, the restoration was completed. In 1833, the city of Bath hired George Phillips Manners, a local architect, to restore the abbey and .he made several major changes. Outside, the towers were altered and flying buttresses were attached. Inside, an organ, galleries, and more seating were added. In 1863, George Gilbert Scott began another major restoration. The organ was moved to the north transept, more pews were added, and a wooden ceiling over the nave was replaced with stone fan vaulting. During the Second World War, the church was not hit, but a bomb dropped nearby badly damaging the large east stained-glass window.

It is a huge church, covered on every wall and floor from one end to the other with writing and tombs. Six hundred and thirty-five memorials fill the walls, some portraying death, others life.

Most commemorate people from the 1700s and 1800s. The floor is made up of 891 flat gravestones called ledger stones. There is also an unusual chandelier, and colorful stain-glass windows with a multi-winged red devil. All of those things are impressive, but the most beautiful thing in the church is the ceiling with fan vaulting. It was created in the 1500s by the king’s master masons, with the stone vaults forming beautiful fan shapes.

After leaving there, we were getting hungry and thirsty. We found an open food market down one street and couldn’t resist a fresh pistachio cream cannoli. So we found a café in an alley and sat for quite a while to rest and have tea and pastry. Then we walked to an outdoor flea market, but as it was after 4:00, most of the booths were shutting down. Then we went to an indoor market, but they were also closing. However, there was one used paperback stall that caught Vere’s attention and he found another book. We walked to Bridge Street where the River Avon flows. There, three successive shallow falls drop to another into crescent curves. I was reminded that the name of the little café where we sat while the laundry was getting done was called The Crescent. The water was soothing, with seagulls whirling above, the water flowing below, and the afternoon sun casting a golden glow on the buildings across the river.

The best time we could get for our dinner reservations at our chosen restaurant in Bath was for 5:45, as we knew we would finish fairly early when the sites closed, and we wanted to eat somewhere different than our hotel. We arrived a half hour earlier than booked, but they were able to seat us. The restaurant was called Chez Dominique, the only French restaurant on our trip. Vere had the steak with Béarnaise and pommes frites, and a glass of Sauternes. I had the risotto verde, which was actually Italian, but it had slivers of asparagus and peas, and was swirled with pesto oil. Then we shared a dessert of cheesecake with strawberries marinated in Moscato wine. Everything was very good. Now sated and exhausted, we returned to our car and made our way back to Cheddar. When driving through the gorge, we saw brown hairy goats with horns and brown shaggy sheep, as both inhabit the rocky cliffs.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.