The next morning, once again in our hotel, Vere had an English Breakfast and I had pancakes, only this time they were not like crepes, they were a bit thicker, but still not as much as we fluffy as we would eat in the US. Different cook, we figured. Today, a note about toast. The British don’t refer to toast as white or wheat, they say white or brown. Brown is simply a whole meal bread or malted grain. It is not the heavier brown bread made with treacle. As an aside, it’s interesting to note that in Cockney slang, “brown bread” means “dead.” Like we might comment regarding someone about to make a bad move with, “he’s toast.”

After breakfast we drove to the cathedral city of Wells, only eight miles southeast of Cheddar. It is a small city with a population of a little over 12,000 and has been a city since medieval times. It was named for the three wells within its city limits. It began as a small Roman settlement but grew with the cloth-making trade, as its port along the River Axe enabled goods to travel. This trade shifted to cheese production and marketing in the 19th century. Its church eventually grew to be the large cathedral we see today.

When we arrived, we got a good parking space next to the cathedral, but first we walked across from it to see Vicars’ Close. Vicars’ Close is unique in that it is the oldest intact medieval street in Europe that goes nowhere, as a “close” is a dead-end street. It was built in 1348 to house the Vicars’ Choral, and it continues to be inhabited by their successors today. It is only 460 feet long, and on either side, in total there are twenty-seven residences, with a chapel and a library at the north end.

Then we crossed back across the street and went to the cathedral, standing like a Gothic castle with a wide expanse of green lawn across its western front. Built with yellowish-white oolite stone, the church is known as “the most poetic of the English Cathedrals.”

The present cathedral was begun about 1175 on a new site to the north of an old minster church. Bishop Reginald de Bohun brought the idea of a revolutionary architectural style from France, and Wells was the first English cathedral to be built entirely in this new Gothic style. The first building phase took about eighty years, building from east to west, and about three hundred of its original medieval statues still remain.

The present cathedral was begun about 1175 on a new site to the north of an old minster church. Bishop Reginald de Bohun brought the idea of a revolutionary architectural style from France, and Wells was the first English cathedral to be built entirely in this new Gothic style. The first building phase took about eighty years, building from east to west, and about three hundred of its original medieval statues still remain.

The first thing we saw when we went inside was an art installation that hung over the nave bathed in pink light. Each was a prayer folded as a dove, asking for peace in Ukraine and in Israel.

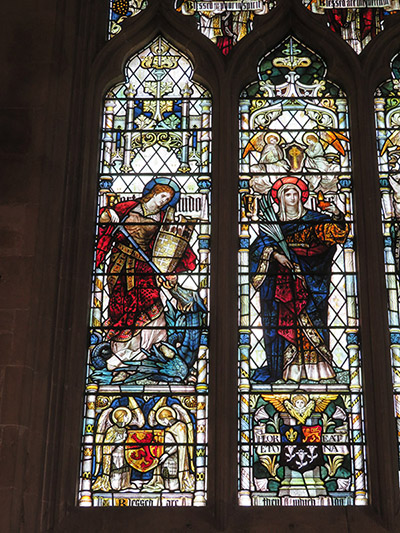

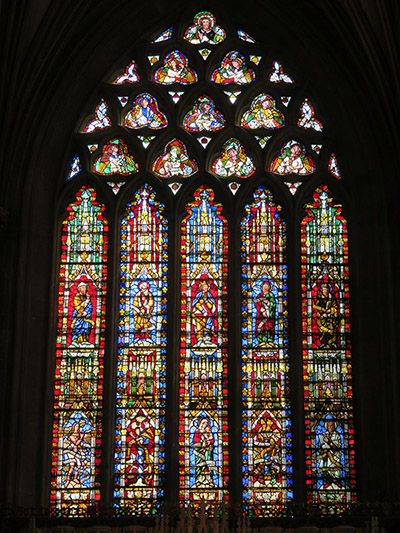

There are several special things to see inside. One is the still-intact 14th century stained glass Jesse Window; one of the best examples in Europe, showing how medieval glaziers designed and created stained glass, but there were many other beautiful windows.

There is the Cathedral Clock, considered to be the second oldest clock mechanism in Britain to survive in its original condition and still in use. The original works were made about 1390 and the clock face is the oldest surviving original of its kind anywhere. When the clock strikes every quarter, jousting knights rush around above the clock and the Quarter Jack bangs the quarter hours with his heels.

Then there are the huge architectural Scissor Arches, added later inside as an engineering solution to a large problem. In 1313, a high tower, topped with a heavy lead-covered wooden spire, began to weigh down the base and show cracks. Thinking it might collapse, in 1338, master mason William Joy came up with the solution to both strengthen and hold the two sides of the cathedral together with a rounded X-like structure.

There are beautifully constructed arched cloister hallways and decorative windows. The eight sided Chapter Room was equally beautiful with an old fanciful Gothic wooden door, fan ceiling and lace-like windows.

We were also able to take steps down into the crypt where several tombs of past Bishops were displayed, one of them more skeletal than formal.

But there were also beautifully carved marble statues at the base of memorials. This one was our favorite.

It took over an hour to walk around inside this huge cathedral, as there are so many side chapels and halls. Then we walked next door to the Bishop’s Palace and Gardens which have been home to the Bishops of Bath and Wells for over 800 years.

This stunning medieval palace is entered through a portcullis, has a flagstone drawbridge and fourteen beautiful acres of gardens. Hailed as a “palace of enchantment,” included are the well pools from which the city takes its name. Although home to the bishop and other families, we were able to walk through a number of rooms within the palace, see their private chapel, the now-empty great hall on an upper level, and all around the gardens with a stream that forms from the well and spills all around the castle forming a moat. The moat had a family of swans with four gray cygnets swimming about. A family of mute swans have been there since the 1800s.

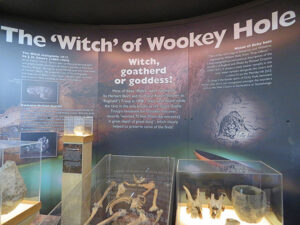

We took a break for lunch at a nearby pub, got cash at an ATM, there called “cash points,” and then Vere wanted to go to the Wells and Mendip Museum. Aside from housing the Wells City Archives with material going back 900 years, there is a library and exhibits. The museum tells the story of the Mendip landscape and its inhabitants. There is a large selection of geological and archaeological specimens, and social history artifacts. On the ground floor is the Balch Room, which has child burials to Stone Age tools, and talks about the Wookey Hole, a local cave. There is also the Netherworld of Mendip, about the history of caving and cave diving, and more specifically what is beneath the Mendip Hills. And there are the remains of the Jurassic Sea Dragon, an ichthyosaur that was discovered in the Liassic rocks of Glastonbury. On the next floor, were statuary and hallways telling the story of early cathedral stonemasons. There was the geology room with samples of local rocks, fossils, and minerals; a collection of 18th century samplers, many made by children; Wells City Galleries of history from King John to 20th century industries; and the Trench, which was an immersive walkthrough experience, with the sights and sounds of a First World War trench of 1914-1918. It included a cartoon of the Women’s Land Army training center in Pilton.

After a short rest, while driving back to Cheddar, we at last decided to visit Cheddar Gorge. We parked in a small lot and bought tickets to Gough Cave. The cave featured stalagmites, stalactites, and fall formations created over 500,000 years ago. We saw the metal racks where the large rounds of cheddar cheese are held in the cave, and the site where Cheddar Man’s 10,000-year-old skeleton was discovered in 1903. The cave was well-presented, with just enough lighting to show the main features. There were also manikins of the men who had discovered the cave. The cave dripped with water in many places and was nice and cool. Very few people were in the cave while we were there, making it more of a private exploration.

Then we went across the street to the Museum of Pre-History, which described how the ancient people of the caves in the area lived during the last Ice Age. Also about the archaeologists, paleontologists, and anthropologists that explored and helped to explain its history. The museum was full of exhibits and did a good job of sharing what the scientists learned about the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer Cheddar Man skeleton. Apparently, the man was in his twenties, stood five feet and five inches, had dark brown skin, blue eyes, and was lactose intolerant!

We took a short break for a cool drink at a café next to a nearby stream and listened to it happily bubbling along. In the midst of the stream, we saw a sword that had been thrust into a stone. Obviously someone’s desire to keep that story alive.

We took a short break for a cool drink at a café next to a nearby stream and listened to it happily bubbling along. In the midst of the stream, we saw a sword that had been thrust into a stone. Obviously someone’s desire to keep that story alive.

Then we visited a few shops that sold cheddar cheese, tasted some samples, and bought some local mead and cheddar straws to nibble on. We had booked a restaurant for dinner in the gorge, La Rocca Italian. It was busy and noisy, but we got our reserved seats and enjoyed dinner. Vere had lasagna and I had Pollo Dolcelatte. Dolcelatte is a soft, blue veined Italian cow’s milk cheese with a slightly sweet taste. It was melted over the chicken with a sprinkling of pine nuts and served with new potatoes. We both preferred my choice.

We returned to the Bath Arms and packed up some things to ship to the US, as we sometimes do when we’ve made purchases abroad and don’t want to tote them along for the rest of our trip. This offloads some worn clothes that we don’t want to carry and helps cushion things that we ship.

That night we experienced the Friday night motorcycle cavalcade that goes back and forth along the gorge road. The road that runs in front of the hotel is the main road that weaves in and out through the gorge. It is also the main road that large trucks use to make their transport deliveries, so days and especially Friday and Saturday nights can be noisy. Since the hotel is a heritage building, the windows cannot be changed out, which means that they can still be opened for fresh air, but they are not soundproof. The hotel did leave packages of ear plugs in each room for this reason.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.