The next day was Thursday, and since we had a bit of a drive, we got up earlier than usual and went downstairs for breakfast. I had muesli cereal with a banana and Vere had pancakes with fruit. Allow me to segue a bit here on the topic of the British pancake. Throughout our trip, we experienced a surprising difference in pancakes whenever we had them. This morning they were very much like crepes. In London, they were very nearly an inch thick, like a real cake, being spongy. Granted they called them a sticky toffee pancake, but there was nothing sticky or toffee-ish about them. At no time did we have a pancake similar to ones we eat in the US. The US pancake has a raising agent like baking powder or baking soda, whereas a crepe does not and that’s why they are flat and thin. To add to that, in the US there is also the southern pancake called a flapjack, hotcake or griddlecake, but in England a flapjack is a caramelized baked chewy dessert bar made with oats, butter, sugar, and golden syrup. Oftentimes it also has a layer of fruit jam in the middle. Later, we tried one filled with raspberry jam and another time with rhubarb. So if you are ever in England and order British pancakes, know that you will get what is closer to what we call a crepe.

After breakfast we were off to Dunster Village to see Dunster Castle, which sits within the northeastern edge of Exmoor National Park. Originally, Dunster Village was comprised of several Iron Age hillforts, and was a Saxon parish, which grew up around the castle and became a center for the wool and the cloth trades. In Old English “Dun” is a hillfort and “tor” is a hill. Within the town there are many old manors, fisheries, a 1,100 year old priory, and a Benedictine monastery.

Dunster Castle sits on a hill and is considered an old motte-and-bailey castle. Which is to say, it is a European fortification with a stone keep on a type of raised hill called a motte, with a walled courtyard called a bailey, and has around it a protective ditch and fenced wall.

In the 11th century, after the Norman conquest, a man named William de Mohun built a timber castle with a stone keep on the hill. Nothing remains of the de Mohun’s castle except the 13th-century lower-level gateway with its massive iron-bound oak doors. He sold the castle to the Luttrell family in 1376, whose family line retained ownership until the late 20th century. Generations expanded it into a family manor. In 1617, it became a Jacobean mansion. In the 1680s, a grand staircase was added. Another bout of building occurred during the 1760s with some Gothic additions.

In 1867, George Luttrell inherited the castle and had a well-known architect, Anthony Salvin, redesign it into a Victorian home. During the following five years, the chapel was demolished, two new towers were added, and the battlement kept its medieval origins. He relocated the kitchen and added corridors and sleeping quarters for fifteen servants, an underground reservoir, a conservatory, gas lighting, a billiard room, a library, a justice room (where disagreements and local cases were heard), and new bedroom suites with bathrooms that had hot running water. Also added were new artwork from the 16th and 17th century, two brass Italian cannons, and a stuffed polar bear, which is no longer on display.

Later, his grandson Alexander Luttrell added a polo field, and the land around it was used for hunting and shooting. Then in 1943, the castle was used as a home for injured American officers. After Alexander’s death in 1944, his son Geoffrey, left without money, had to sell the castle and land but still remained as a tenant. In 1954 the family was able to buy them back, but in 1976, Geoffrey’s son Walter Luttrell gave it over to the National Trust.

When we first arrived, we opted for a separate special tour of the downstairs. That tour took us on all the lower levels. There was a large kitchen with its original wooden counter, two black iron stoves inserted into the wall, a large pantry, buttery, washing room, and other storage areas below the house.

We learned a lot about life on the lower levels with the servants. In particular, a long line of bells were still fastened high on a wall, for when the servants were called to a certain room.

Then we were able to walk through the house, which is still fully furnished on two floors. The hand guide was clever in that for every room, a story was told as if the owners were in the room and you learned what they were doing, thinking, and who they were hosting. The view from the hilltop from the back balcony looks down upon green expanses sprinkled with white fluffy sheep. Beyond, one can see the Bristol Channel and a deer park that was stocked in the Victorian period.

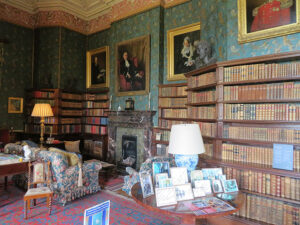

There are many rooms to see at the castle: a reception hall with its huge fireplace and geodesic designed ceiling; a sitting room where tourists are invited to sit and read about the family history; the dining room with family portraits; the master bedroom with a robe laid out on the bed; the amazing library, which has been at Dunster Castle since the 17th century, with its unusual walls covered in colorful wallpaper embossed to simulate leather; and the green tea room next to a conservatory full of plants.

Some of the most amazing things at the castle are the incredible carved banisters along the grand staircase. It was built in 1680, with each panel carved from a single piece of elm. The intricate carvings depict a fox and stag hunt, some Charles II shillings, and a trophy of arms which commemorate Colonel Francis Luttrell’s military career, all surrounded by acanthus leaves. Below, to the left of the staircase are glass cabinets that display medical herbs and medicines.

In one room there are very rare painted calfskin leather wall hangings, made between 1701-1741.

They tell the love story of Antony and Cleopatra, all dressed in medival dress with European ladies in waiting. The image is embossed to give a three-dimensional appearance. Leather hangings were often chosen for dining rooms over more traditional tapestries, as leather doesn’t retain the smell of food.

After walking through the house, we decided to take a break, walk down the path to the village and have lunch. We would be able to return with our tickets. We stopped at a small deli. Vere had a bacon, stilton and caramelized onion panini on Ciabatta. I had a veggie tart with salad and humus. I decided to try a raspberry shake, which turned out to just be raspberry syrup in milk, but with a good stir it was good. We also tried a raspberry flapjack bar.

The village had one main street, on which we walked both sides. We stopped to look at the old Dunster yarn market building in the center of town, which is a 17th century timber-framed, octagonally round, open market hall, noted as a monument to Dunster’s once-flourishing cloth trade.

We went into a few shops. One was a gallery, where a man had painted medieval designs on cloth. They were beautiful, but I would like to have seen real tapestries. Then we went into an antique shop, and what do you know, a tapestry was half tucked into a chair. I pulled it out and unfolded it. It was three by five feet, depicted a garden with three noble women and one noble man, surrounded by leafy trees, flowers and birds. It was delightfully charming, and the front was in excellent condition. There was some damage on the backing cloth, but that could be replaced. When the woman told me it was twenty-five pounds, I nearly fainted. In any other store, a tapestry that size would have sold for at least five times that. I bought it and smiled all the way out the door.

Then it was back to walking the castle grounds. Around the castle are gravel pathways that weave between beautiful gardens all in bloom. A map outlined all the pathways to choose from.

We chose to walk along the river garden, filled with huge Chusan palms and plants with gargantuan leaves.

We passed needle leaved Yew trees, and – shock – a few Sequoia trees! There was also the Handkerchief tree in bloom, which has light green leaves, but also long, white leaves that hang down like a kerchief. The seeds were brought from Australia. Amazing flowers were in bloom along the way, along with some inventive art works.

Additionally, we came to a working flour watermill, and lovely foot bridges that crossed over the stream.

We stopped at a tearoom and Vere had a cream tea. For those unfamiliar with British teas, a cream tea doesn’t just mean milk in some tea. It includes a scone, clotted cream and jam. Sometimes also with butter.

Along the path and extending over the swift moving stream was the Lover’s Bridge, an 18th century rustic stone, arched foot bridge, which included a brick seat built into it at the top. There we took a picture of ourselves and watched the pretty brook rush by.

After we made our way back, we checked out the bookstore, which was adapted from the 17th century stables, some of the oldest ever held by the Trust. The wooden box stalls are still there, all painted white, lined with books and gifts.

When we were on our basement tour, the guide mentioned nearby Cleeve Abbey, only ten minutes away. Since it was on our way back to Cheddar, we decided to stop and see it. We drove through the ancient abbey gatehouse at the beginning of the property and parked.

With our English Heritage membership, we got in free. It was 4:00 and for the next hour, we were the only visitors there.

The Cistercian abbey of Cleeve was founded in 1198 with money from the Beckerolles family and William de Mohur of Dunster. Twelve monks and Abbot Ralph first inhabited what was officially named Vallis Florida “Flowering Valley” Abbey, but as Cleeve Village was so nearby, most knew it as Cleeve Abbey. A stream runs through the lower part of the property, so it is easy to understand that the abbey was once surrounded by a water-filled moat. The abbey has been described as once having the finest cloister buildings in England. The walkway under cloister roofing is gone, but a wide open grassy area delineates where it was.

Although the abbey’s church was destroyed by Henry VIII during the dissolution in 1536, much of the abbey is still there. The gatehouse, passageways and many of the walls and upper stories are still there or have been revamped for visitors. In the large upstairs 15th century refectory, still with great beams stretching across the roof line, the vaulted ceiling still had carved images of angels looking down. The great dormitory is one of the best examples in the country for its period. An exhibition and virtual tour told the story of the abbey and daily life for the holy men that once inhabited it, supported by the export of wool. We visited the refectory, dormitory and chapter house, going up stairs twice to a second level to see different chambers, one with surviving painted walls. We could see a depiction of the crucifixion, Saints Catherine and Margaret, and a man standing on a bridge over water with fish, and angels hovering at his head. A lion approached from one side of the bridge and a dragon on the other.

We also saw where the large church used to stand, but now, only the base of the pilings are left, in a vastness of green grass. On the back side of the abbey ruins was a relatively new covered building. It was put in place to protect a remarkable 13th century floor with heraldic tiles still intact. The tiles are what are called encaustic, which means that their pattern and figures are not produced from a painted glaze, but from different colors of inlaid clay. The decorations shown were of the coat of arms of Henry III, Richard the 1st Earl of Cornwall, and the Clare family; thought to be celebrating the 1272 marriage of Margaret de Clare and Edmund the 2nd Earl of Cornwall.

With an overcast sky, the afternoon coming to a close, and only the two of us there as visitors, it felt like a haven of peace and tranquility. We finished just as it was closing. We headed back to our hotel, where we once again had dinner in the dining room.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.