Up early the next morning, we went to breakfast right around the corner, to a place called The Pilgrim. The walls were covered with copies of Modigliani paintings. It made the place look obviously modernistic with his impressionism, but also most of the figures looked pale and a little sad. Not exactly the mood one wants to begin their day with, but at least the owner was able to display copies of the artist’s work.

That brief stay of only one day in London was just the beginning of our trip. We would spend more time in the city at the end of our trip. We returned to our hotel, got our packed bags, now with dry clothes, and rolled the bags to Paddington Station to head to the county of Somerset. The train ride was a pleasant two hours with no rain. We watched the countryside go by, and saw lots of angled sections of green farmland, and a tan deer in a brown field, only noticeable when it twitched its ears.

When we arrived in Bath, we had to get a taxi to Enterprise car rental on the outskirts of town, which turned out to just be a one-room confirmation hub. A young man took us in a car further out of town to a commercial development on the site of a former chocolate factory where the car was waiting. The final paperwork was done in the public parking lot. The car was of the small size we had asked for, and included GPS, which most European countries charge extra for. Granted it was standard stick, but unless one wants to pay a lot extra for an automatic, this is usual. It also had the name Enterprise in large letters across the car doors. This was not something we would normally agree to, as rental cars tend to get broken into more. In smaller towns, rental agencies are likely to have a limited number of cars, no matter what you may have ordered beforehand, things can change.

When we arrived in Bath, we had to get a taxi to Enterprise car rental on the outskirts of town, which turned out to just be a one-room confirmation hub. A young man took us in a car further out of town to a commercial development on the site of a former chocolate factory where the car was waiting. The final paperwork was done in the public parking lot. The car was of the small size we had asked for, and included GPS, which most European countries charge extra for. Granted it was standard stick, but unless one wants to pay a lot extra for an automatic, this is usual. It also had the name Enterprise in large letters across the car doors. This was not something we would normally agree to, as rental cars tend to get broken into more. In smaller towns, rental agencies are likely to have a limited number of cars, no matter what you may have ordered beforehand, things can change.

Driving on the left side of the road only takes about an hour or so to get used to, and since Vere had lived in England, he knew how to drive with the steering wheel on the right side and to stay to the left side of the road. As in many places in England, the roads in Somerset are narrow. Many times the striped white line disappears and the road is only wide enough for one vehicle, but usually there are places along the way where one can pull over to let the other car or truck pass. It’s not as comfortable for Americans who are used to wider roads, and we were surprised to see higher speed limits than we would dare to reach on some roads. One simply has to get used to the narrow roads and add extra caution on blind curves.

Forty minutes later, we were driving through the base of the Mendip Hills and into one of England’s most iconic natural landmarks, Cheddar Gorge. The wide green landscape began to open up with the road heading down between a divide in the flats, until the limestone cliffs rose up high to the left and right. People were on both sides of the narrow road; walking, climbing, and picture taking. Wild brown sheep were on the side and in the middle of the road and goats were on the hillside.

Cheddar Gorge is really very small when comparing it to America’s Grand Canyon. But for England, it is extraordinary, with prehistoric archaeology, cliff-top walks with far-reaching views, and two cave systems. One can also experience adventure caving, wildlife spotting, rock climbing, freefalling in a cave in the Black Cat Chamber, and they even have an escape room. Most of the site is owned by the National Trust, but the south side is owned by the marquess of Bath’s Longleat Estate. Between the two, it is well maintained.

Why is it called Cheddar Gorge? And no, it is not from the cheese. It comes from the old English word ceodor which means “a deep dark cavity or pouch.” A Neolithic skeleton 10,000 years old was discovered in 1903 in one of the caves and named the Cheddar Man. And then, yes, later, the cool steady cave temperatures made it good for storing cheese, which was then named cheddar after the gorge. There will be more on Cheddar Gorge and the cheese later, when we spend the day there.

For now, we were on to our first place of stay located in the village of Cheddar, which is situated south of the gorge. The village has old roots, dating to the Roman and Saxon eras, and has several historic sites: Saint Andrew’s Church, which has been there from the 11th century; small remnants of a 941-1200 C.E. royal hunting lodge, used by Kings Edmund, Edgar, Henry I and Henry II; remains of a Roman villa under the Vicarage garden; the Kings Head Inn, built in the 17th century; the Market Cross, which was a 15th century preaching cross and parish stocks; ruins of a Saxon palace and Medieval chapel of Saint Columanus; and many other 16th and 17th century inns, cottages, and homes.

We were booked at the Bath Arms for six nights. The hotel was built in the 1930s, replacing an old coaching inn called “The George” built in the late 1700s.

Our room was on the second floor up long stairs, so there was no elevator. We prefer a king-size bed, but one was not available for the week, so we got two twins. The bedroom and the bathroom were large. There was one desk and one chair. This is always a bit of a struggle for us, as Vere often works on the road and I write every day. So every time we arrive at a hotel, we have to figure out two places to work at. Many times, I simply sit in bed with the laptop on my lap.

The rooms were named, some after birds and others after plants. Ours was the Goldfinch Room. I was curious about why a goldfinch was chosen for the room. There are many meanings, but in the positive vein, the goldfinch is reputedly a bringer of good health, resilience, joy, happiness, good fortune, and prosperity. After the challenges with our arrival, this was good news. The bird’s unusual call sounds like “bay-be” or “po-ta-to-chip.”

That evening we ate in the hotel. I was determined to eat something with authentic local cheddar cheese. Cheddar cheese is the most popular cheese in both the UK and in the US. In the US, cheddar comes in mild, medium, sharp, extra sharp, white, New York style (aged twelve months with a hint of bergamot), and Vermont cheddar (made from milk not treated with rBST and aged three month). Most US cheddar cheese is processed, mixed with other cheeses such as Colby and different cheese curds. Annatto coloring turns the cheese orange and is used to cover any differences in appearance that milk fat from different cheeses can produce, keeping the color uniform; and the cheese is vacuum-packed. Most English cheddars are cloth-bound and open-air cave aged. England classifies their cheddar as mild, medium, mature, extra mature, or vintage. British cheeses are an off-white or natural color as they don’t use annatto coloring. Also interesting to note, even though cheddar cheese is produced in many places around England, only one company, the Cheddar Gorge Cheese Company, ages cheese in the Cheddar Gorge Caves.

We had planned to eat at the hotel dining room several times for convenience, and breakfast was included with the room. That evening I had the cream of cauliflower soup and a crumpet with melted cheddar cheese. Vere had the roasted duck, which came with a few green beans, a stack of thin-sliced scalloped potatoes, and a small flavorful pie with minced meat inside.

He said the duck was tender and good, but the pie outshined it. We also opted for dessert. Vere had the brownie with cherry sorbet and I had the sticky-toffee pudding. How could we come to England and not enjoy this iconic dessert? The cake was warm and good, but it did not come with the usual sticky toffee sauce. Instead they offered chocolate syrup, which I declined. How could they not offer the correct sauce which makes the dessert? Disappointed, I had some caramel ice cream, instead.

Breakfast the next morning was good. The Bath Arms had a short but varied menu. Vere reverted to his early days in England of having a full English Breakfast, which includes bacon and pork sausages, two eggs, a grilled tomato, fried mushrooms, toast, and baked beans. The thought of all that was too much for me, so I had a couple of scrambled eggs and toast. We were quite at home, having our usual tea for breakfast.

Our first site to visit was Lacock Abbey, which was to the east, actually just over the border from Somerset into Wiltshire county. The village is smaller than Cheddar, but more picturesque with medieval buildings lining the few narrow streets. At the entrance to Lacock Abbey is the Fox Talbot Museum, which tells the story of the birth of photography. William Henry Fox Talbot was a mathematician who was also interested in chemistry, botany, astronomy, and he was the pioneer of Victorian photography.

Our first site to visit was Lacock Abbey, which was to the east, actually just over the border from Somerset into Wiltshire county. The village is smaller than Cheddar, but more picturesque with medieval buildings lining the few narrow streets. At the entrance to Lacock Abbey is the Fox Talbot Museum, which tells the story of the birth of photography. William Henry Fox Talbot was a mathematician who was also interested in chemistry, botany, astronomy, and he was the pioneer of Victorian photography.

In 1835, he took the first image of a window at the abbey where he lived, with a small “mousetrap camera,” and now that photograph is known as “the world’s earliest surviving photographic negative”. The museum is housed in the 16th century barn that was the abbey’s stables. Double doors exit the museum to a long winding pathway that takes one to the abbey. Even on the approach from a distance, the abbey stands out as a beautiful stone manor house across a green expanse.

The abbey was founded by Countess Ela of Salisbury, a well-placed Middle Ages woman, who had served as the Sheriff of Wiltshire. She then became the first abbess of the Augustinian Abbey in 1232. Her 1225 copy of the Magna Carta came with her to Lacock and remained there until moved to the British Museum in 1946. Abbess Ela served there for seventeen years, until her death in 1261. The building has seen two major changes. Abbess Ela’s original cloister was demolished in the 1400s, but what we see today is still a rare example of Medieval monastic architecture.

Little is known about the abbey between the mid-1300s to mid-1500s, aside from a book of parchment fragments of financial accounts that recorded the business of the abbey in the wool trade. When King Henry VIII declared the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536 to 1541), the church’s liturgical objects were taken, the church was destroyed, and the abbey was purchased by Sir William Sharington, a Tudor courtier, in 1540. He had served the king in several posts and had become a member of parliament. He was the first to make changes and turned the abbey into his private country manor house. He kept the cloister, built a three-story octagonal tower, constructed the stables, and added Italian-inspired Renaissance architecture.

He was able to do so because of his position as a moneylender and a merchant with several ships that dealt in the wool trade. In 1548, he began to embezzle money from the Bristol Mint. Then he got involved with Lord Thomas Seymour in a plot to begin an armed uprising to overthrow the government and to kidnap King Edward VI, still a young boy. The plot was discovered, both were arrested, Seymour was beheaded, but Sharington got a man named Francis Talbot, 5th Earl of Shrewsbury, to plead his case for him. Sharington was then pardoned, and after paying a large sum, was able to recover his estate, and ended up becoming the Sheriff of Wiltshire in 1552, for one year until his passing.

A successor of the Earl of Shrewsbury, John Ivory Talbot, acquired Lacock Abbey in 1714, from his grandmother Olive Talbot. It was under his supervision that the abbey saw further changes, this time in the Gothic style. He added an entrance arch to the property, remodeled a gallery on the south side, added windows, and a Great Hall.

The dining room was in green and his study in blue.

The property was retained by the family for the next two hundred years, but in 1944, Matilda Talbot passed the estate on to the National Trust.

Other unusual items were found at the abbey. Aside from the parchment fragments on the wool business, a 14th century book, hand-written on parchment in Latin was found, called the Expositiones Vocabulorum Biblie, written by William Brito. It gave explanations for difficult words found in the Bible. There were other items of furniture and decorative pieces on display that showed Sir William Sharington’s wealth. One was an octagon-shaped table with a marble top made for his octagon tower. It is supported upon a cross-shaped base, where four satyrs sit with fruit baskets on their heads.

I was deeply interested in the history of this manor, as it was part of my research for my next book, Abbey of the Whispering Maidens. While walking through the abbey, I stopped and spoke with many of the guides seeking information on original drawings of the abbey from the 1200s & 1300s. Many of the volunteers were full of information about the house and I will be sure to thank them in my acknowledgement. We walked all around the abbey’s ground floor, but the kitchen, half of the cloister, and all of its upstairs were closed to the public. On occasion these areas can be opened but only if there are enough volunteers to monitor them. We were at one end of the cloister when a volunteer was showing two others where bats had settled in the roof of the closed cloister walkway.

The cloister was still in excellent shape. When the cloister was decorated in the Gothic style, known as Perpendicular, the newer arches were adjusted to line up with the vaulted ceiling.

The cloister was still in excellent shape. When the cloister was decorated in the Gothic style, known as Perpendicular, the newer arches were adjusted to line up with the vaulted ceiling.

Masons created whimsical bosses (ornamental knobs), of medieval images and symbols, to cover these joints. Such figures were a mermaid with a treasure box, a woman with a ring and book, a man with a bow and arrow, a spotted goat, a dog with bared teeth, and a rooster.

After we walked through the house, we went outside and walked dirt paths. There were floral beds on either side of the paths, all filled with white flowers. The smell got my attention first, as we were walking next to a profusion of wild garlic fully in bloom, with its short, wide, and pointed leaves. Standing taller among them, also in full bloom, were the white tuffs of garlic mustard.

The acreage also featured a wide grassy meadow where sheep were grazing, a fishpond, a rose garden not yet in bloom, an orchard where there were bee hives, and vistas of wide meadows, all fit for a perfect manor retreat. The abbey has been used as a backdrop for many films and TV dramas, including Harry Potter, Pride and Prejudice, and Downton Abbey. The timeless nature of the architecture makes Lacock Abbey the perfect background location for such works.

Finally satisfied with viewing what we could and even given an email to reach a historian for more information on the early abbey, we left. We walked into the village for lunch at the Red Lion, in a 200-year-old Georgian building.

Vere had the Henry burger with – of course cheddar cheese and Henry’s relish burger sauce. I had the baked camembert, melted in its own wrapper in the base of its small round wooden cheese case, served with more relish and toasted sourdough bread.

Afterward, we walked more of the village. Down one narrow and crooked medieval street, filled with wood and plastered ancient homes, some very much on a tilt, we found St. Cyriac’s Church. Within was a chancel dedicated to William Henry Fox Talbot, erected in 1902. That portion of the church, called the lady chapel, was by far the oldest looking with dark medieval cross beams and decorative caps with odd creatures.

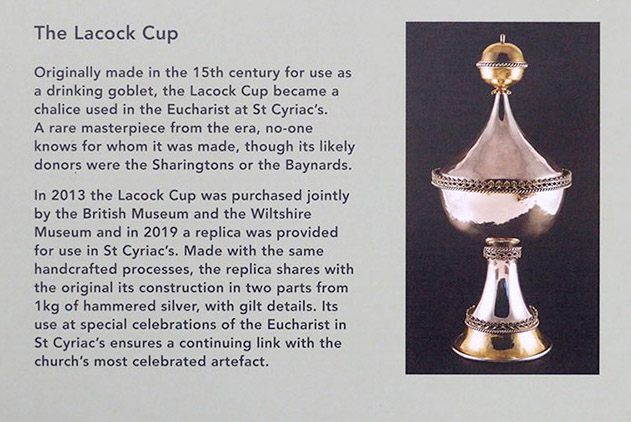

There were two other things of note in the church. One was the Baynard Brasses, found on the floor of the Lackham Aisle, which showed Robert Baynard (c.1430-1501) and his wife Elizabeth Ludlow, praying. She is dressed in the robes of a lady of the manor and he in the full regalia of a knight. There was also a replica of the Lacock cup, which you can read about below.

Outside we noticed this stone buzzard on the eaves overlooking the graveyard.

After a full day in the spring sunshine and having gotten a good look around the abbey and the town, we headed back to Cheddar Village. That night we ate dinner again at the Bath Arms restaurant. Vere had the well-seasoned pork and chicken pie with a golden crust, which came with mashed potatoes and broccolini. I had a small tart with salmon and spinach with spears of asparagus and a poached egg on the top. The restaurant is quoted as saying that everything is “seriously” good. And it was.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.