This Friday morning we had another good breakfast, and then took our time before driving to the cathedral city of York and capital of Yorkshire. We found central parking downtown where we could walk to everything. The street view shows the old gate and the York Cathedral towers in the back. Our first stop was the York Art Gallery.

They had a special exhibition with Monet’s The Water-Lily Pond, but we had seen it in Paris for the second time last year, so we went one floor up to see the ceramics, glassware and fine art. First, there was the Wall of Women, a new display that had opened on International Women’s Day the week before. The Centre of Ceramic Art celebrated the innovations and creativity of women working with clay from the early 20th century to the present.

In the rest of the ceramics collection there were more than 3,000 pieces from the 1600s through the 1900s, including Rockingham, Creamware, Delft and Toby jugs. Toby jugs are ceramic pitchers that are modeled into amusing animal or people characters. There was also a large collection of Chinese and Korean bowls, plates, and vases, dating from 1700 until 1900, and glasses, pewter, copper, silverware, and clocks from the 18th and 19th centuries.

One of my favorite pieces in the museum was an extravagant highly-decorated clock, featuring moving figures and sound, dating from the 1780s. The clock chimes every quarter of an hour and the figure of Hercules at the top strikes the hours. When the automaton is activated, the four dancing figures at the base of the temple at the top spin around and the stars above rotate. The interior glass rods also revolve to give the impression of a waterfall. A procession of twenty-six figures moves across the front of the clock, while at the back, more figures are seen crossing a bridge between two water wheels.

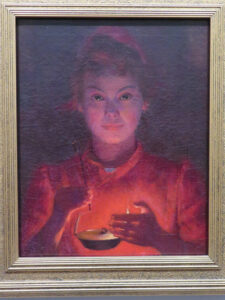

What we really went to the museum for were paintings from the 14th to the 19th centuries. The gallery’s collection of over 1,000 paintings is exceptional for its range covering the history of Western European painting. There were early gold-painted church altarpieces, 17th century Dutch morality paintings, and 19th century French paintings by artists working before and at the same time as the Impressionists. British paintings, dating from Elizabethan times to the present day, included a particularly good collection of 17th and 18th century portraits, and a group of Victorian narrative paintings. As well, there were thousands of drawings, watercolors, sketches, doodles, letters, and prints, known as “works on paper.” Half are landscape views and a good number of them are by York local artists, among them Henry Cave, John Harper and John Browne. We also saw: William Etty’s, Preparing for a Fncy Dress Ball; Albert Moore’s, A Venus; Amy Atkinson’s, The Lamp; and among them was Bartolomeo Cavaceppi’s, Young Centaur Tempted by Love.

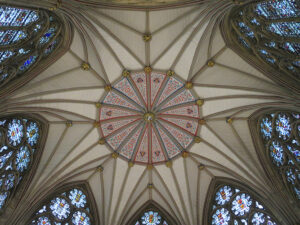

After the gallery, we walked to the York Minster Cathedral, which is one of the world’s most magnificent. Its handcrafted stone is beautifully rendered, and its medieval stained glass is unrivalled. It is hard to get a full picture of the entire Cathedral as it is so large, but it also had scaffolding along its right side, and a large tree is directly in front of it. There are also some curious carvings along its outer walls. But the interior is breathtaking with soaring arched ceilings.

Here’s a quick look at its history. In 633, it began as a small stone church built around a wooden one. In 733, it got its first Archbishop, Ecgbert, but the church got burned down in 1069. In 1080, Archbishop Thomas of Bayeaux had a new one built, and each successive archbishop added on to it. A stained-glass window was constructed in 1226 showing Archbishop William Fitzherbert on a horse being declared a saint. King Edward III married Philippa of Hainault in the church in 1328. In 1405, Archbishop Richard Scrope was found guilty of treason and killed, but he is buried there. In 1644, the town of York surrendered to parliamentary forces, which protected the church from harm. But then over the next two hundred years a series of fires burned different parts of the church, which had to be rebuilt. During zeppelin raids and the Second World War, more than eighty windows were removed to save them and later returned. From 1967 to 1972, money was raised to reinforce the foundations and repair stonework. In 1997, York Minster was the first UK church to have female choristers, and in 2005, it was the first UK church to have a Black archbishop.

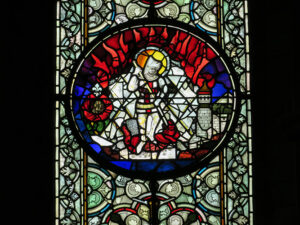

We took over an hour to explore this huge church, along with visiting the crypt. First, there were many stained glass windows: The Great East Window; a window showing St. George slaying a rather puny dragon; and there was a set of three windows featuring the seven-headed beast with ten crowns, which is thought to represent the demonic and powerful authority of the state. The red dragon represents Satan. There were museum display cases and two items caught our eye. One was a medieval carved drinking horn. The other was an ivory casket from 1148, believed to be the personal reliquary of St. William of York, which once held the heart of a crusader. There was also a very large fan-shapped wooden chest, called a Cope Chest that once stored Bishop’s capes.

There was a large clock inside that sounded every quarter of an hour. It has two knights that strike on the quarter hour. There was also a memorial honoring past soldiers with an odd ancient astronomical guide to the stars.

The most impressive part of the cathedral was the Chapter House, an octagonal room surrounded by stained glass windows and with a tiled floor, arched painted ceiling, and the many bizarre creatures around the walls.

We were also able to descend into the crypt where we saw a couple of unusual things. One was a room with several tombs. A prominent one was for Saint William Fitzherbert of York, who it is said performed miracles. A mannikin stands at its head, dressed as a bishop with raised hands in benediction. And a curious and gruesome carving called the Doomstone. It is from the first Norman Minster, which the curators believe might have been attached to the front of the old 12th century church. It shows the “mouth of Hell,” where lost souls are slowly pushed into a boiling cauldron by devils and demons, and it is decorated with toads, which the people of the day thought to be magical creatures of the night.

Aside from those items, hundreds of beautiful memorials were all around the church. One in particular was quite lovely. The Minster also recently added a large statue of the Queen Mother, in honor of her life.

By then we were hungry, so we found a French restaurant called Côte York. Since it was late, we decided to make it a late lunch/early dinner.

For starters, Vere had the chicken liver parfait with pink pepper butter, fig compote, pickles, and toasted sourdough baguette. And I had the cheese soufflé, topped with Camembert, served with an herb cream sauce. For mains, Vere had the fillet with Béarnaise, fries, and a salad. And I had the baked ratatouille with Crottin goat cheese from the Loire Valley with white haricot beans, topped with a circling of thinly sliced zucchini, served with sourdough toast. Both were very good.

For starters, Vere had the chicken liver parfait with pink pepper butter, fig compote, pickles, and toasted sourdough baguette. And I had the cheese soufflé, topped with Camembert, served with an herb cream sauce. For mains, Vere had the fillet with Béarnaise, fries, and a salad. And I had the baked ratatouille with Crottin goat cheese from the Loire Valley with white haricot beans, topped with a circling of thinly sliced zucchini, served with sourdough toast. Both were very good.

Now full and rested, we walked down The Shambles, a historic, cobbled street with timber-framed medieval buildings leaning every which way. It was full of fun shops, including the store from the Harry Potter franchise called “The store that shall not be named.” It was chock-full of Potter stuff, but none of it was for us. We did find a sweet shop and bought some peanut brittle and chocolate.

Then we walked to the Castle Museum a few blocks away. This place is famous for being the oldest indoor street of its kind in Britain, called Kirkgate. It is named after the museum’s founder, Doctor Kirk, who was a medical doctor with an interest in the past. As some of his patients were poor, they often paid him with objects they owned. He wanted to give visitors the experience of going back in time to a bygone age. Like a real street, Kirkgate is made of buildings and shops based on places that operated in York between 1870 and 1901. This was a time when York was already attracting tourists with luxury shopping, but it was also a place of extreme poverty. Everything, from the lampposts to the horse troughs, are original items from the Victorian period and earlier. Very few props are replicas, even the carriages are original, and so are nearly all of the shop fronts. There is a pharmacy, jewelers, a grocer’s, and coach and horse in the street, the draper’s shop with its bolts of cloth, a brass shop with a curious rams head, a toy shop full of toys and games, and a gift shop from the final decades of the 19th century.

The museum first opened in 1938, but the building dates back to 1780, and was built to expand the overcrowded York County Gaol. The space now occupied by Kirkgate was the exercise yard and was open to the sky. This building became known as the Female Prison, but there were plenty of male prisoners kept here too. The oldest part is a large timber-framed building, now the Barton’s sweet shop, but it was originally built in Stamford, Lincolnshire, in the 16th century. In 1890, it was a butcher’s shop, and in the 1930s it was taken apart and brought there to be a part of the museum. Now all is under a roof.

Around the back of Kirkgate, we visited the Rowntree Snicket, which housed the poor dwellings and the candlemaker’s. (A snicket is a passageway between walls or fences.) Making candles was a smelly business as the cheaper candles were made of rendered animal fat. Unpleasant and dangerous businesses existed side-by-side. In the late 19th century, many York families lived crowded into single-room homes with no kitchen, bathroom, or running water. Rowntree Snicket is named after a man named Seebohm Rowntree, who made a report about the poverty in York. The Snicket and the poor dwellings are based on his team’s findings.

There were also the Moorland Cottage period rooms, which represented life on the North Yorkshire moors in the middle of the 19th century. The family all lived in one room where they slept, cooked, and ate, and in foul weather, also worked. The women worked a spinning wheel, sewed, recycled scraps of fabric and old clothes to make bed quilts and patchwork cushions on chairs. Near the front of the room, on the floor, was a domed basketlike structure called a bee skep, a type of beehive used in Yorkshire for over a thousand years. The wooden and metal box next to the skep was a honey press, and the white fabric bags on the table were honey strainers. All this was so they could harvest and sell the honey. There was a folding screen, used for privacy when getting dressed and washing. Two things were decoupaged, the screen and a witch ball hanging in a window. Traditionally, witch balls were used to repel evil forces, but by the middle of the 19th century many were used as ornaments. There was a ceramic container called a salt pig. Salt was used to preserve and flavor food, and as a cleaning element. There was a linen press for clothing and bedsheets, and a rabbit hung from a rafter ready to be prepped and eaten.

After that room, there were several others that showed how people of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries lived.

The museum on two levels took over an hour to walk through. Then I went through the gift shop while Vere went to explore another exhibit of 1914 about the first World War. It told about the process, from the recruitment office to the horrors of the frontline, from rats to foot rot, and shell shock to gas warfare. When done, we headed back to our B&B.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.

The official website of Lita-Luise Chappell, writer on sex, magic, food, distant lands, and everyday life with articles, poetry, novels, travelogues, rituals, cookbooks, and short-stories.